4 Reasons Unda is Ingenious in Ave Verum Corpus

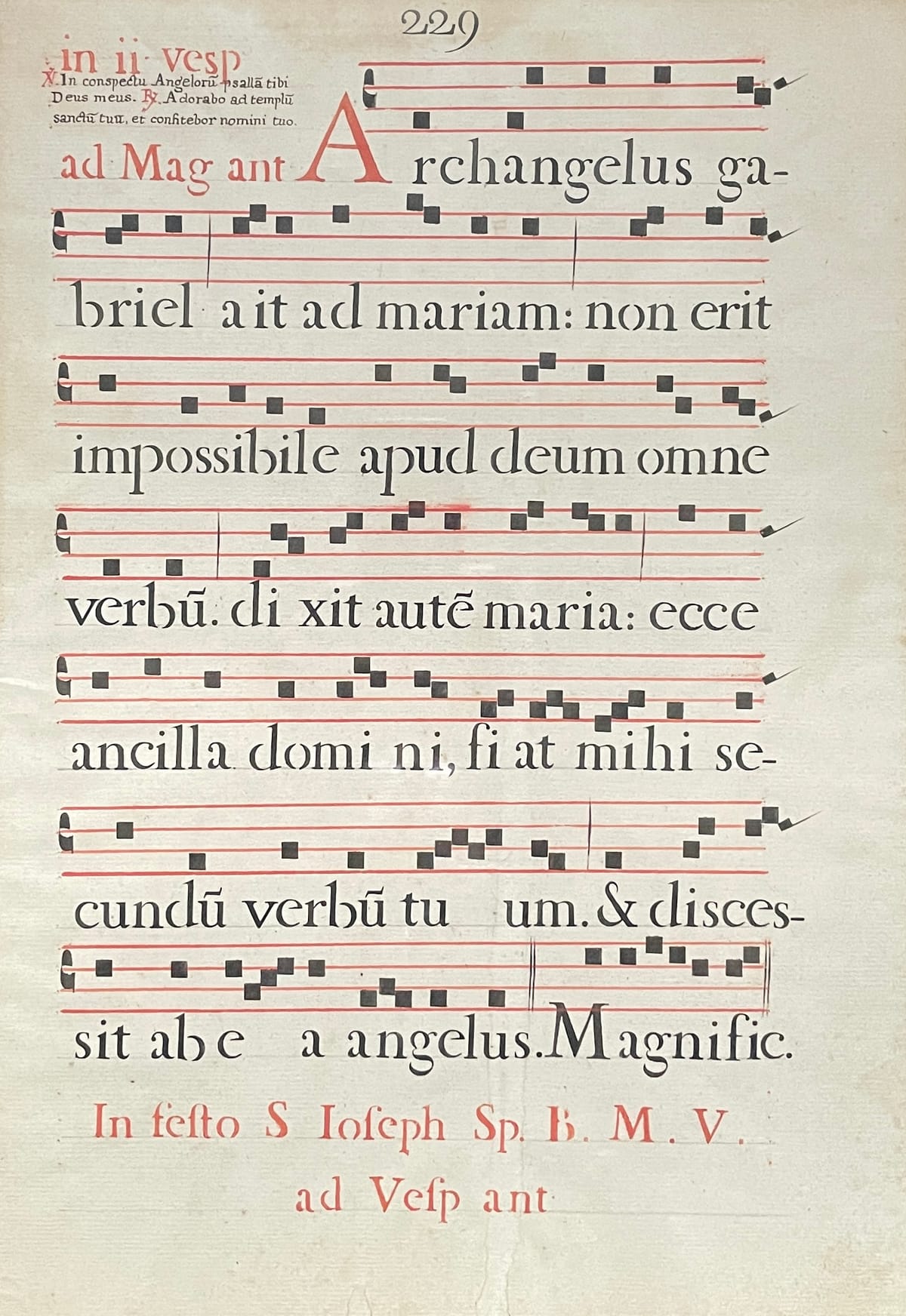

The four main lines of Ave Verum Corpus originate at least from the 1300s, attributed to Étienne Aubert, better known as Pope Innocent VI.

Ave, verum corpus natum de Maria Virgine;

Vere passum, immolatum in cruce pro homine:

Cuius latus perforatum, unda fluxit sanguine;

Esto nobis praegustatum in mortis examine.

The poetic use of unda in the third line is ingenious for four reasons:

- Unda suggests a host of biblical passages on the significance of water in Christ's sacrifice: from Ezekiel's immersion to experience the eschatological Temple (Ezekiel 47.1-12), to John's accounts of both the death of Jesus and the revelation of the Re-Creation (John 19.28-37 and Revelation 1.7 & 22.1-2). Also see Psalm 22.12-21; Isiah 53; and Zechariah 12.10.

- Unda holds a double meaning. It may be translated as both whence (adverb), and water (noun). Thus, the poet conveys the flowing of water from Christ's body with the singular word, unda.

- By its multivalence, unda economically retains the pattern of 15 syllables in 8.7 meter for all four main lines. Thus, 60 syllables total.

- By its preservation of the metrical rhythm, unda helps create a numerological symbolism: In the ecclesiastical calendar, the intended use of Ave Verum Corpus is in the annual Mass of the Blessed Sacrament (a.k.a. Corpus Christi) which falls on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday which is the 8th Thursday after Easter Sunday — exactly 60 days after Easter!

Other literary structures to notice in the four main lines:

- The first word of each line is 2 beats.

- The second word of each line is 2 beats.

- The third set of beats is 4 beats fulfilled by one or two words.

- The middle of each line is marked by the assonance of -atum.

- The end of each line is marked by the assonance of -iné.

Here's a literal word-for-word translation:

Ave, verum corpus natum de Maria Virgine;

Hail, true body born of Mary Virgin;

Vere passum, immolatum in cruce pro homine:

Truly suffered, sacrificed on (the) cross for humanity;

Cuius latus perforatum, unda fluxit sanguine;

Whose side pierced, whence water flowed (with) blood;

Esto nobis praegustatum in mortis examine.

Be (for) us (the) foretaste of death weighing.

O Jesu Dulcis, O Jesu Pie, O Jesu Fili Mariae,

O Jesus Sweet, O Jesus Pious, O Jesus Son (of) Mary,

Miserere mei. Amen.

Have mercy (on) me. Amen.

While the original Latin plainsong utilized a unison melody, the medieval lyrics have been set with varying complexity and moods by many composers. Certainly the ethereal solemnity conveyed by William Byrd (1605), is to be preferred over Mozart's lighthearted setting.